ON THE 1921 TULSA RACE MASSACRE

BOMB MAGAZINE

by Kalup Linzy

A project organized by Kalup Linzy, featuring contributions by Sarah Ahmad, Lex Brown, Crystal Z Campbell, Adam Carnes, Joy Harjo, Tina Henley, Quraysh Ali Lansana, Phetote Mshairi.

On the graves of the genocide and on the backs of the enslaved—Tulsa, Oklahoma never lets me forget how this country was built.

Before I relocated to Tulsa in 2019 to participate in the Tulsa Artist Fellowship, I was aware of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre that decimated a thriving Black neighborhood but completely unaware of how it would haunt me. After landing in the city and getting oriented, I found myself unable to sleep for the first week. I understand this is an experience most people have when they relocate to a new place permanently. However, my intention at the time was to engage with the city for two or three years and then move on. Considering I have partaken in over a dozen artist residencies, I understood my restlessness was not anchored in the life or place I had left behind but by the fact that I was now residing on ground zero: My apartment was and still is located on Detroit Avenue and Archer Street, where the Greenwood District and Tulsa Arts District meet, and my thoughts were with those ancestors who had lost their lives or their livelihood there.

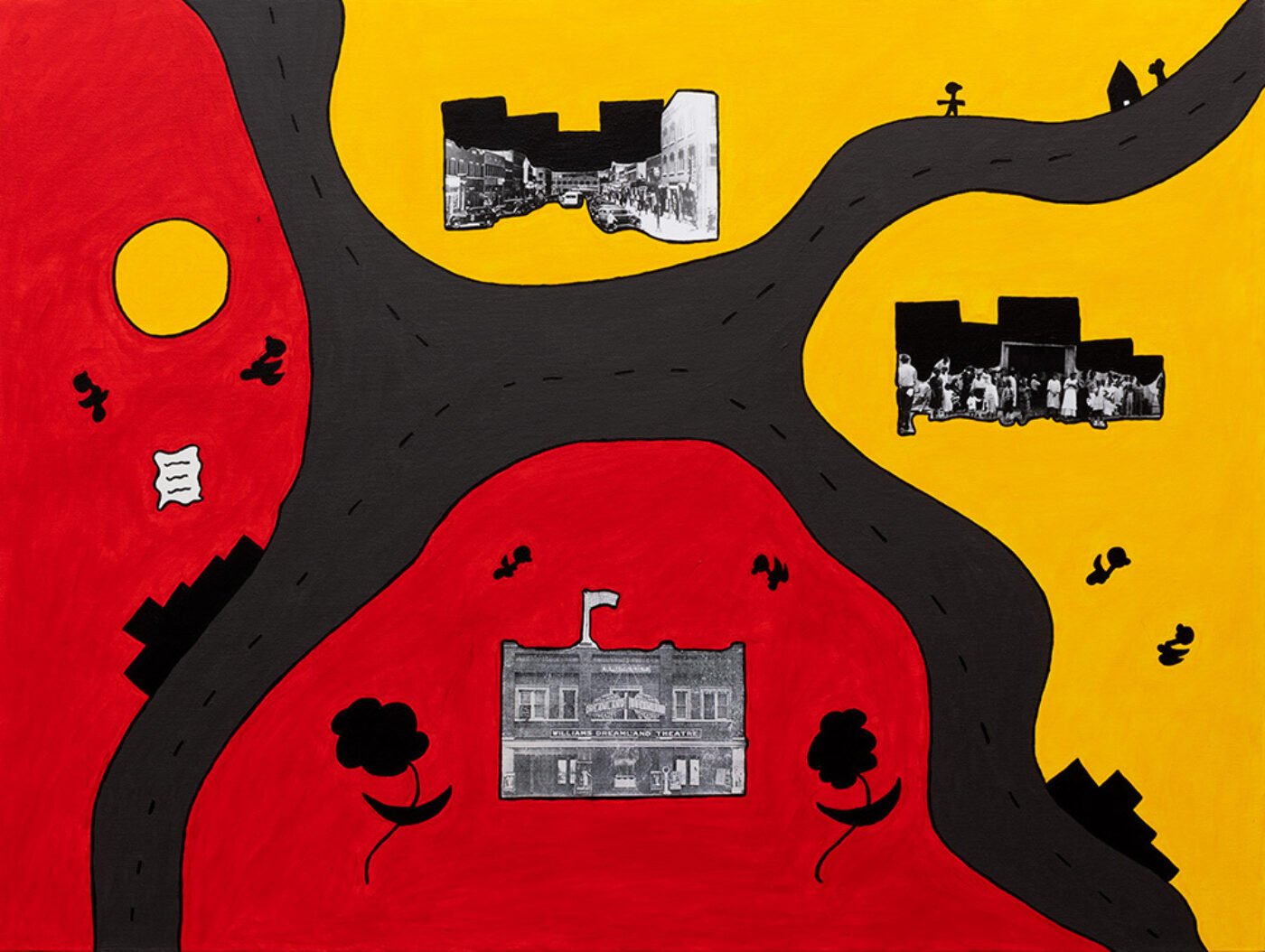

Dreamland—1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, 2021, mixed media, 16 × 20 inches. Photo by Kevin Todora. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Horton (Presents), New York.

The Tulsa Race Massacre took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, many of them deputized and armed by city officials, attacked Black residents and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It has been called "the single worst incident of racial violence in American history.”Ellsworth, Scott, “Tulsa Race Riot,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, 2009. Accessed 31 Dec. 2016.The attack, carried out on the ground and from private aircraft, destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the district—at that time the wealthiest Black community in the United States, known as "Black Wall Street."

More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals, and as many as 6,000 Black residents were interned in large facilities, many of them for several days. The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead. A 2001 state commission examination of events was able to confirm 39 dead, 26 Black and 13 white, based on contemporary autopsy reports, death certificates, and other records. The commission gave several estimates ranging from 75 to 300 dead.

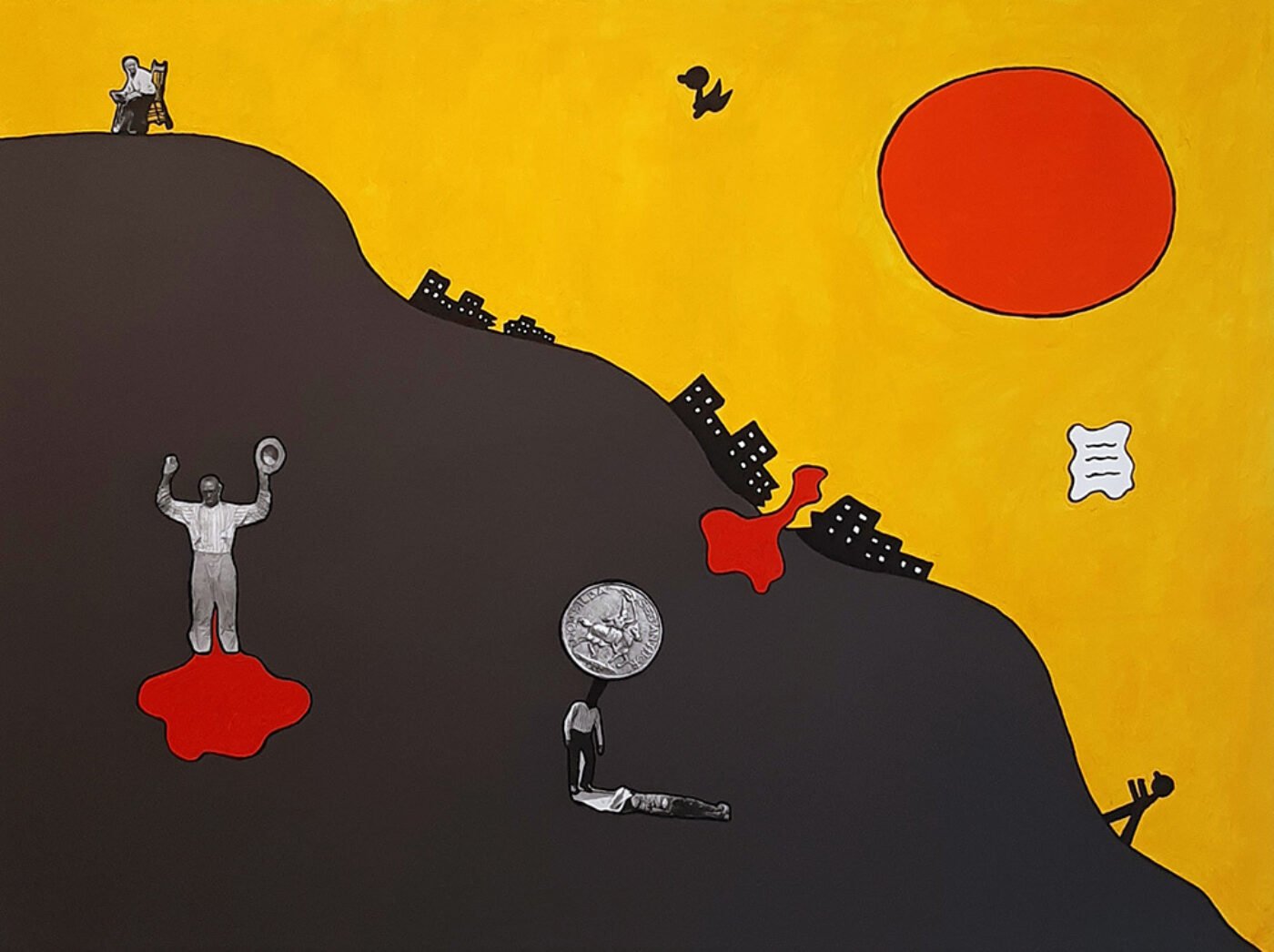

Sunny Side of Black Wall Street—1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, 2021, mixed media, 48 × 36 inches. Photo by Kevin Todora. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Horton (Presents), New York.

Within ten years after the massacre, surviving residents who chose to remain in Tulsa rebuilt much of the district. They accomplished this despite the opposition of many white Tulsa political and business leaders and punitive rezoning laws enacted to prevent reconstruction. [The Greenwood district] continued as a vital Black community until segregation was overturned by the federal government during the 1950s and 1960s. Desegregation encouraged Black citizens to live and shop elsewhere in the city, causing Greenwood to lose much of its original vitality. Since then, city leaders have attempted to encourage other economic development nearby.“Greenwood District, Tulsa.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation. Accessed 13 May 2021, wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenwood_District,_Tulsa.

During my first year and a half in the city, preceding the pandemic, I spent time getting acquainted with artists and residents who were from Tulsa or had been residing here for a while. One thing became evident: the city’s politics were neither monolithic nor black and white. Some people welcomed the new direction the city was moving in and others opposed it. My goal was to negotiate where I would fit and whether or not I should stay. I was all too familiar with the story of white women inciting violence after crying rape or claiming they were attacked by Black men, usually when they were caught having an affair. Or of white supremacists orchestrating terror attacks when they feel threatened by Blacks’ economic and political power. I was raised in Florida and schooled on the Ocoee Massacre (November 2, 1920), the Rosewood Massacre (January 1–7, 1923), and the Groveland Four (July 16, 1949).

Before the Rosewood Massacre, the town of Rosewood had been a quiet, primarily Black, self-sufficient whistle stop on the Seaboard Air Line Railway. Trouble began when white men from several nearby towns lynched a Black Rosewood resident because of accusations that a white woman in nearby Sumner had been assaulted by a Black drifter. A mob of several hundred whites combed the countryside hunting for Black people and burned almost every structure in Rosewood. Survivors from the town hid for several days in nearby swamps until they were evacuated by train and car to larger towns. No arrests were made for what happened in Rosewood. The town was abandoned by its former Black and white residents; none ever moved back, none were ever compensated for their land, and the town ceased to exist.

“Rosewood Massacre.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation. Accessed 4 Apr. 2021, wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosewood_massacre.

Sunny Side of Black Wall Street, The Sequel—1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, 2021, mixed media, 48 × 36 inches. Photo by Kevin Todora. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Horton (Presents), New York.

John Singleton’s 1997 historical film Rosewood was based on these events.

The Ocoee massacre was a white mob attack on African American residents in northern Ocoee [a town in Orange County, near Orlando], which occurred on November 2, 1920, the day of the US presidential election. Most estimates total 30 to 35 Black people killed. Most African American–owned buildings and residences in northern Ocoee were burned to the ground. Other African Americans living in southern Ocoee were later killed or driven out on threat of more violence. Ocoee essentially became an all-white town. The massacre has been described as the "single bloodiest day in modern American political history."Paul Ortiz, “90 Years After the Ocoee Election Day Race Riot,” Facing South, 14 May 2010, facingsouth.org/2010/05/ocoee-florida-rememberingthe-single-bloodiest-day-in-modernus-political-history.html

The attack was intended to prevent Black citizens from voting. In Ocoee and across the state, various Black organizations had been conducting voter registration drives for a year. Black people had essentially been disfranchised in Florida since the beginning of the 20th century. Mose Norman, a prosperous African American farmer, tried to vote but was turned away twice on Election Day. Norman was among those working on the voter drive. A white mob surrounded the home of Julius "July" Perry, where Norman was thought to have taken refuge. After Perry drove away the white mob with gunshots, killing two men and wounding one who tried to break into his house, the mob called for reinforcements from Orlando and Orange County. The whites laid waste to the African American community in northern Ocoee and eventually killed Perry. They took his body to Orlando and hanged it from a light post to intimidate other Black people. Norman escaped, never to be found. Hundreds of other African Americans fled the town, leaving behind their homes and possessions.

I’m Coming Up—1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, 2021, mixed media, 48 × 36 inches. Photo by Kevin Todora. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Horton (Presents), New York.

You can find YouTube clips of my great-uncle, the late Rev. Fred Maxwell, retelling his firsthand experience witnessing Mose Norman visit my great-grandparents Benjamin and Alzada Maxwell in Stuckey, Florida, my hometown, before heading to New York City where he lived out the rest of his life until his death in 1949.

The Groveland Four (or the Groveland Boys) were four young African American men—Ernest Thomas, Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd, and Walter Irvin—who in 1949 were falsely accused of raping 17-year-old Norma Padgett and assaulting her husband on July 16, 1949, in Lake County, Florida. Thomas fled and was killed on July 26, 1949, by a sheriff's posse of 1,000 white men, who shot Thomas over 400 times while he was asleep under a tree in the southern part of Madison County. Greenlee, Shepherd, and Irvin were arrested. They were beaten to coerce confessions, but Irvin refused to confess. The three survivors were convicted at trial by an all-white jury. Greenlee was sentenced to life because he was only 16 at the time of the alleged crime; the other two were sentenced to death.

Press On—1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, 2021, mixed media, 20 × 20 inches. Photo by Kevin Todora. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Horton (Presents), New York.

During the weeklong raid, the Ku Klux Klan descended upon Stuckey. My aunts and uncles have retold their experiences, outlining the terror. The furor that erupted sent families scattering for safety, some to never return. White men in trucks and cars sat near both entrances of our town and watched who came and went. Mob members shot into the homes of Matthew Maxwell and Joseph Maxwell, who were my great-uncles, the brothers of my grandmother who raised me. The mob shot into the home of my great-uncle Joe, who had recently returned to Stuckey from World War II, simply because they were angry that Black veterans had gone out with white women during the war. My great-uncle Fred recounted to a local newspaper that my great-grandmother Alzada was so disturbed by the incident she died with it on her mind. She could never understand why the white men would do that to them when they never bothered anybody.

After much consideration, I decided to stay in Tulsa for two years, completing my fellowship and applying for the Tulsa Artist Fellowship Arts Integration Award. This past fall, I was awarded the grant, which will support the launch of the Queen Rose Art House, an artist residency and social space that will host three to four out-of-town artists each year. The project will commence this summer, one hundred years after the Tulsa Race Massacre.

I could not allow this moment in history to pass without commemorating and honoring those who lost their lives or livelihood as a result of white supremacists’ pursuit of dominance.

I invited eight artists I admire to contribute works in response to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: Sarah Ahmad, Lex Brown, Crystal Z Campbell, Adam Carnes, Joy Harjo, Tina Henley, Quraysh Ali Lansana, and Phetote Mshairi. They are all currently based in or have deep family connections tying them to Tulsa.

Kalup Linzy is an interdisciplinary artist and a Tulsa Artist Fellowship Arts Integration Grantee.